Written by Ross Mumford, Reviewed by Heather Medlock, Images added by Kaylee

Fashion is more than clothing: it is a language that reveals history. Every era has its own distinctive style, which mirrors the values, customs, and social dynamics of that time. Edwardian fashion of 1900–1919 is no exception. Clothing worn during this period speaks volumes about the world that existed before the First World War—a world preserved, in part, by Titanic’s 1912 voyage.

Fashion as Social Identity

When Titanic departed from Southampton, England—with stops in Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland—she carried 2,208 passengers and crew. What each person wore offers insight into their social status, personal means, and access to trends.

In Edwardian society, the divide between classes was distinct and permeated every aspect of life, including clothing. Class was reflected in the quality of fabric, tailoring, ornamentation, and access to modern styles. The cut of a gentleman’s suit or the embellishment on a lady’s hat could silently reveal their placement on the social ladder. Though styles were generally similar across the board, those in higher social classes had access to finer materials and current trends from London, Paris, and New York.

However, not everyone on board Titanic wore the latest looks. Just like today, Edwardian people dressed in what was accessible, affordable, and appropriate. Many in 1912 wore clothing tailored in styles from previous years. Staying up-to-date with trends required disposable income and access—two luxuries most passengers in the lower classes simply did not have.

Hallmarks of Edwardian Fashion

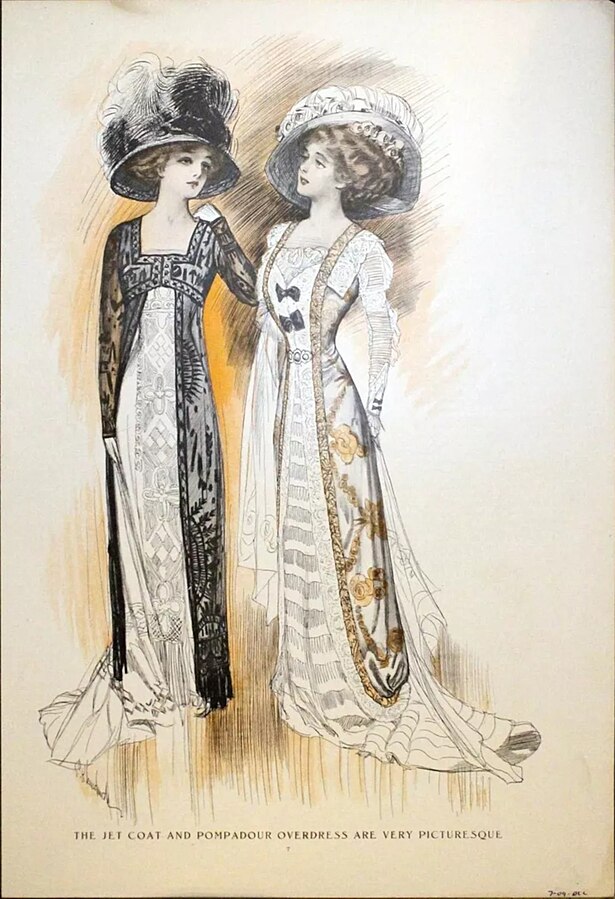

Fashion in the Edwardian Era, often referred to by the French term la Belle Époque (“The Beautiful Epoch”), was defined by elegance, grace, and refinement. Women’s clothing emphasized the idealized feminine silhouette, marked by narrow waists, flowing skirts, and delicate, lightweight fabrics.

The popular “S-curve” silhouette of the early 1900s created an exaggerated posture by pushing the hips back and chest forward. This look was made possible by a new, “healthier” corset that offered more support and was less restrictive than its Victorian predecessor. Around 1910, however, this shape began to shift. As women became more active in work, sports, and suffrage, they needed clothing to reflect their changing lives. Fashion evolved into a more straight-lined silhouette with less structure, though the corset remained a key component of a woman’s wardrobe.

The “Gibson Girl” look, made famous by artist Charles Dana Gibson’s illustrations—and later, the “Fisher Girl,” illustrated by Harrison Fisher—came to embody the ideal Edwardian woman: beautiful, confident, and active. Her hair was piled into a voluminous updo, and her wardrobe reflected a balance between elegance and modern independence. First-class passenger, model, and actress Dorothy Gibson became a celebrated “Fisher Girl” just a few years prior to boarding Titanic.

The wardrobe of the average first-class woman included whalebone corsets, tailor-made ankle-length skirt suits, white blouses, afternoon tea gowns, fur stoles and muffs, and hobble skirts. The look was elevated by trimmings, embroidery, and ornamentation available to women of the upper crust. Lace was especially popular, as its intricacy and delicacy echoed the era’s feminine ideal. However, the level of detail depended heavily on a woman’s ability to afford such craftsmanship.

Edwardian hats were often elaborate and enormous: wide-brimmed and adorned with ostrich feathers, flowers, and ribbons. Accessories were just as important as garments, with jewelry, gloves, parasols, and handbags completing each ensemble. Women would change outfits up to six (or more!) times per day, often assisted by personal maids. Over twenty women passengers on Titanic brought along maids to maintain their wardrobes.

Nearly all male passengers on Titanic, regardless of class, wore suits in some variation. Even during the day, full suits were expected. However, the difference between a simple third-class suit and one tailored by a Savile Row clothier was instantly noticeable to the discerning eye. Like their female counterparts, upper-class men changed several times a day depending on the activity. Evening dress codes were strict, and white-tie attire was standard for elite social events.

Men’s hats were a strong visual indicator of class and occupation during the Edwardian Era. Top hats, made from stiffened silk or high-quality beaver felt, were reserved for formal occasions and worn almost exclusively by the upper class. Bowler hats, with their rounded, durable felt crowns, were commonly worn by the middle and upper-middle classes, especially clerks, professionals, and city workers. For the working class, the duncher cap—also known as a flat cap or newsboy cap—was standard. Made from wool, tweed, or cotton, these soft, rounded caps were affordable, practical accessories worn daily by laborers and many third-class passengers on board Titanic.

As one moved down the decks of the Ship, the amount and quality of clothing decreased. Third-class passengers often had only a few outfits, which they wore for several days between washings. Buying new clothes was a rare luxury, and many relied on sewing, mending, and repurposing their garments. Most clothing was handmade, as factory-produced goods were still emerging in accessibility and affordability.

Fashion Icons on Board

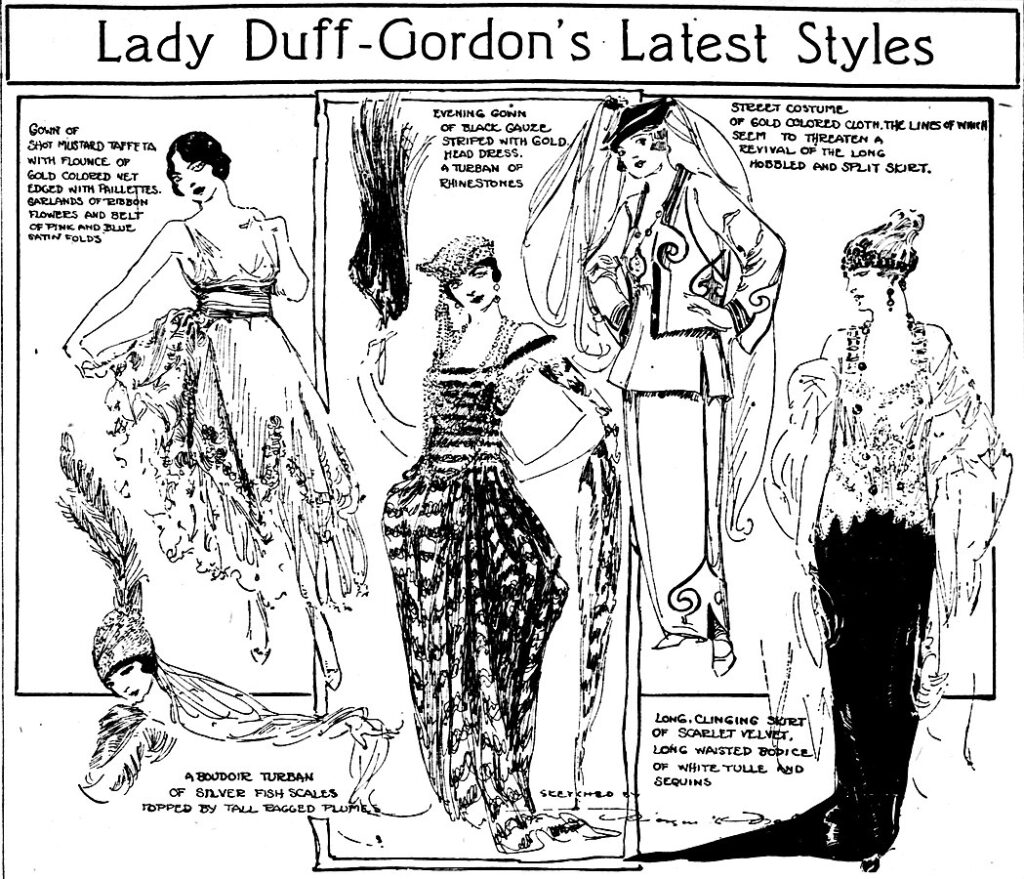

One of the most influential fashion figures on Titanic was Lady Lucile Duff-Gordon, a first-class passenger and successful fashion designer. She ran the fashion house Maison Lucile, which had locations in London and New York. Lady Duff-Gordon is credited with several fashion innovations, including the introduction of the split skirt, holding the first formal fashion shows with trained models (“manikins”), and designing contemporary lingerie. Though the Duff-Gordons had not originally planned to sail on Titanic, urgent business in New York prompted them to board the Ship in Cherbourg.

Also traveling in first class was Edith Rosenbaum (later Edith Russell), a fashion journalist, buyer, and stylist. Based in Paris, Rosenbaum regularly reported on haute couture, current trends, new fabrics, and her perspective on the personalities shaping the fashion industry. She boarded Titanic in Cherbourg with numerous trunks filled with designer clothing and orders from her clientele. She is especially remembered for the musical toy pig she carried into her lifeboat, which she used to comfort survivors after the tragedy.

Fashion from the Wrecksite

Some of the most personal and poignant artifacts recovered from Titanic’s wrecksite are fashion related. Since 1987, RMS Titanic Inc. has conducted seven recovery expeditions and uncovered approximately 500 artifacts of clothing and fashion accessories, including hats, shoes, jewelry, and textiles.

These objects require meticulous conservation work, as textiles are extremely fragile, so they often spend the most time in our collections care labs. While not every artifact can be traced to a specific passenger, many offer clues, and ongoing research continues to uncover their owners’ identities and reveal their stories.

Many such artifacts have been displayed around the world as part of TITANIC: The Artifact Exhibition. Each exhibition features textile artifacts, allowing visitors to experience deeply personal and tangible connections to the people who lived—and dressed—during this moment in time.