Life On Board a TITANIC Expedition

Tomasina Ray, RMS Titanic Inc. President and Director of Collections

When I started working with RMS Titanic Inc. in 2012, I was introduced to the eight expeditions to Titanic that the company had completed. I learned about the past 37 years of recovering artifacts, collecting data, and the technology and types of submersibles used. I also heard about the adventure of being on an expedition in the Atlantic, which I experienced firsthand when I joined the 2024 expedition as Project Lead.

A Ship Built for the Task

The experienced Co-Expedition Leaders David Gallo and Troy Launay taught me a lot about expeditions, including lessons I hadn’t seen coming. We set out on the Dino Chouest, a 300-foot anchor handler, on July 12, 2024. This vessel was perfect for the expedition because of its stability in the rough seas of the North Atlantic. The living quarters rose in a tower at the forward end. Aft of the tower sat the giant spools for anchor cable and a specially outfitted area for the two remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and their pilots. Nearby was a customized trailer, converted into a workspace for the data specialists who worked around the clock in loud, hot, tight quarters.

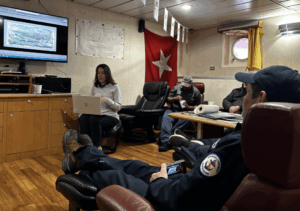

From a lounge on one of the lowest decks, across from the mess, I glimpsed crew members briefly at the beginnings and ends of their 12-hour shifts. For those of us with more flexible schedules, those rooms became our office and meeting space. It was where we reviewed the equipment status, discussed expedition coverage, and adjusted our strategy as challenges arose.

Falling Into Rhythm

Soon, the days settled into a familiar rhythm. My cabin was located just inside one of the ROV launch pads, and each morning, I first peeked outside to check on the ROVs. Ideally, I would see an empty platform, meaning the ROVs were still deep underwater, hard at work. Seeing an ROV on deck was no good. It meant that either a technical or weather concern had required it to traverse the 2.5 miles back to the surface. The expedition was extremely ambitious, and we had a detailed plan for every possible moment the ROVs could be active. Any downtime meant data collection came to a halt. With limited time at the wrecksite, every missed moment meant a lost opportunity to gather valuable information.

Our daily morning meetings offered glimpses into commercial vessel operations. These sessions covered mission progress, upcoming objectives and activities, safety briefings, recognitions, and reminders from Rory Golden, the expedition’s Chief Morale Officer and seasoned Titanic diver and researcher, about the upcoming presentations. Although many of us were already steeped in all things Titanic, the convergence of so many specialties and so much experience created an atmosphere ripe for learning and information exchange. The presentations were valuable not just for the researchers but also for engineers, operations staff, and ROV pilots, helping fuel everyone’s enthusiasm for the mission and bringing the team together.

24/7 Work and Midnight Meals

I spent most of each day working in the lounge, reviewing footage and cataloguing progress. When not working, I went across the hall to the mess, where I could get not only breakfast, lunch, and dinner but also a midnight meal. Something I hadn’t considered was that, because the vessel is fully staffed and operates 24/7, meals would need to be provided for those working the 12 noon–12 midnight and 12 midnight–12 noon shifts. I didn’t make it to many midnight meals, given that I love my 8 hours of sleep, but there were a few nights when conversations went long, and I’d find myself with a plate of chicken tenders and fries at midnight.

When it was time to visit the data and imaging specialists in their working quarters, we had to weave around the boat’s infrastructure and over several raised platforms that had been installed for the ROV operations. This required donning steel-toed shoes and the hard hat I had been issued when I arrived. The large amounts of data being captured and processed meant that computers were running constantly. The specialized data storage machines on board were also extremely loud, and because they couldn’t get too hot, they had their own dedicated AC unit. The space was small and the team laser focused, so we limited our visits to conferring about artifact sightings and searches.

The Moment That Changed Everything

We performed most of our monitoring via several specially installed data streams to the lounge. This feed allowed us to see the ROV pilots’ view of the mission in real time. ROV 326—equipped with LiDAR, sonar, and a magnetometer—operated too high above the seafloor to see much in the total darkness at Titanic’s depths. For image capturing, we relied more on ROV 327, which had an immense lighting system designed by Marine Imaging Technology. From this camera, we could see artifacts, marine life, and the wreck herself, though not to the level of detail that we would achieve once the collected data had been processed.

This real-time footage proved critical on the morning of July 29. We had already been on site for two weeks, scanning and imaging the debris field, when we finally came to the Ship’s bow. For me, this was a moment I had been looking forward to. Having worked with the artifact collection and so many small fragments of the Ship, I was finally seeing the entirety of the structure, live.

As the ROV came up over the prow, I knew that something was wrong. I’d seen the bow of this Ship over and over again in previous expedition footage and documentation, and my collections management brain went into overdrive. For everything recovered from Titanic, we write a Condition Report: we compare each artifact in every exhibition to previous photos and records to check for damage or changes in condition. My brain immediately performed a condition report on the Ship: there had been a change; there was deterioration.

The iconic bow railing, once a symbol of Titanic’s proud silhouette, was no longer intact. A large section from the port side was missing, likely having broken off and fallen over the side of the wreckage. I quickly gathered my safety gear and confirmed with the imaging and data teams that had done a high pass days before that the railing had been missing before we arrived and that it was lying in the mud at the base of the prow.

The Clock Is Ticking

To me, as someone who believes strongly in the importance of preserving the tangible bits of our past, this was a stark reminder that Titanic, though slowly, is deteriorating. We often take her iconic appearance for granted. The wreck will continue to change as the structure weakens and collapses in on itself.

Reflecting on my experience as the expedition’s Project Lead in 2024 and all the history and stories yet to be discovered in the debris field, I feel a renewed sense of motivation and urgency: to preserve the artifact collection, tell Titanic’s stories, and prepare for future recovery missions. The ocean’s harsh conditions are relentless, and if we don’t act, we risk losing irreplaceable pieces of the past. This expedition and future missions are about more than exploration—they’re a commitment to preserving the Ship, uncovering the stories she held, and preventing an important legacy from vanishing forever beneath the waves.